Paul Deakin

For Harlestone Road allotments contact Sandra Motley at motleysandra@aol.com

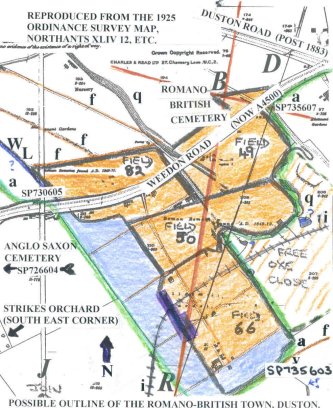

St Luke's Archaeology (SLA, a local archaeology group) has spent seven years of intensive research investigating all that has been written about Duston, including the Romano-British (RB) remains. The group has talked to eyewitnesses about water, finds, and walls uncovered to be hurriedly buried again. It has also walked the area at different times of the day and during different seasons. Due to the imminent development of the Sixfields site, further Northampton expansion, and the possibility of a road through what is believed to be the southern boundary of the Roman town, SLA have been forced to publicise their findings prematurely - three years ahead of schedule.

Above the flood plain of the Western arm of the River Nene, a Belgic tribe, the Catuvellauni, expanded into this area around AD25 and established a sprawling settlement along its south-facing slope, above the river. About 44AD, following the Roman invasion, SLA believes that a 25-acre legionary (vexillation) fortress may have been established.

A north-south road crosses the site (about 13° east of north), while another east-west one crosses above (about 10° south of east) to form a crossroads. Since these do not recognise the possible fortress, it is assumed that this only lasted briefly and little trace can remain. Earth embankments suggest that the town may have gravitated northwards to develop around the crossroads, then spread westwards towards the main villa sites in that direction. To the north, there is an RB cemetery, with a variety of burials including ritual pit shafts, cremations, inhumations. To the West, there is an Anglo Saxon cemetery surrounding an RB mausoleum where a lead coffin was found (1908/1903 discoveries).

Water is believed to have come into the town from the northwest, from the spring line at Duston (where 27 wells served the village in 1906, prior to mains supply). Open leats were observed by eyewitnesses, which ran continually. Furthermore, in 2003, surveyors advised SLA that the natural flow is west to east, probably to a point known as St James Spring. Later (around the 13th to 14th century) it is believed the Augustinian Monks of St James Abbey culvetted the water to their monastery, which they had done for both St James Spring and a well head source towards the adjacent parish of Dallington. St. James Abbey lies next to the RB town to the east and probably used the Roman town as a quarry for the foundations of their abbey, judging from the mix of stone seen in the excavations there recently.

The RB town, including the two cemeteries, has a possible area of 42 acres (17 hectares). Since the cemeteries were about 7-8 acres (RB) and perhaps 4-5 acres (Anglo-Saxon), that allows a township of about 30 acres (divide by 2.471 for hectares). The town appears to have lead an uneventful life from 44AD to conjecturally c540 AD (given the dating of objects found), perhaps acting as a local focus or small roman town (civitas) serving the numerous surrounding villa estates.

It is possible that the River Nene carried enough water to be navigable for shallow draught boats up to this point - even if this was subject to seasonal restrictions. The stone coffin of Barnack stone in the RB mausoleum may have been brought up river. There is a ford below the town, and the river valley would have been full of millions of tonnes of gravel in the Roman period. Intriguingly, the nearby village name of Kislingbury can be interpreted as ‘the fort of the gravel dwellers’, so the town may have been named after this geographical feature, although we have no record of an official name.

The site was, presumably abandoned c540 AD in the recorded plague period, with the possible development of Anglo-Saxon settlements in the areas of clean water, around nearby villa sites. Early churches may have been built on such sites. St Luke's Church, Duston is certainly a candidate, with the proximity of the east-west Roman road.

However, with all of the Roman routes out of the town for several hundred years, the nearby villages of Upton, Harpole, Duston and Dallington must also be possible candidates for Anglo-Saxon sites, (see ‘The Roman Villa’ by John Percival 1976, B.T. Batsford Ltd., 4 Fitzharding Street, London, W1H OAH). Given the loss of continuity of Romano-British names, something quite dramatic must have occurred at this final stage in the sixth centrury.

If the Sixfields site is developed without further research, important evidence and remains may be lost, and the full history of the area may never be known. St Luke's Archaeology (SLA) are asking local people to contact the council planners to support their appeal for an archaeological dig on the site. Write to The Town Planners at Northampton Borough Council, Cliftonville House, Bedford Road, Northampton, NN4 7NR.

This article was kindly contributed by St Luke's Archaeology (SLA).

See Also

Duston in Roman TimesRoman Road in Duston

Map of Romano-British Town

Roman Finds in Duston

Roman Coffins & Other Finds

In 1903 a Roman lead coffin was discovered in the Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Duston, followed by a Roman well in 1905 and finally a Roman mausoleum in 1908, while hundreds of Anglo-Saxon remains were being uncovered in the same area. In the 1970s a mosaic would be reported nearby.

The coffin pictured was found at Duston in 1908 in the Roman mausoleum. It was seven feet below the surface, in a four-foot thick walled enclosure with other skeletons and coffin nails. The enclosure was of local limestone, but the coffin was of Barnack limestone. Perhaps brought up river in view of its size and weight, the coffin was placed in Abington Museum, Northampton, where it can still be seen.

Bronze Head of Lucius Verus

A small bronze head of Lucius Verus, who ruled the Roman empire jointly with Marcus Aurelius (between 161-169 AD) was found at Duston some time before 1870 in the Romano-British cemetery on the northern side of the Roman town. It was designed to be attached to a ceremonial staff, and probably used at a temple site. Such staffs formed part of the regalia of rural shrines and may imply that the imperial cult was included in the rites of the temple.

A small bronze head of Lucius Verus, who ruled the Roman empire jointly with Marcus Aurelius (between 161-169 AD) was found at Duston some time before 1870 in the Romano-British cemetery on the northern side of the Roman town. It was designed to be attached to a ceremonial staff, and probably used at a temple site. Such staffs formed part of the regalia of rural shrines and may imply that the imperial cult was included in the rites of the temple.See Also

Duston in Roman TimesRoman Road in Duston

Map of Romano-British Town

Key to Map

The map is based upon the 1925 edition Ordnance Survey Map (Northants Sheet XLIV 12, etc.). Unfortunately, three sheets join at this point, hence the aberrations.

The green line defines a boundary from the 1722 map, produced by DFG Publishing Ltd in 1990 and consists of a southwards projection of “Arbourfield".

Field 49 is Lady Hadland above.

Field 50 is Lady Hadland, below

Field 66 is Ox-Close Leys

Fields 82 is Thirteen Furlong

(on some Maps, "Free Oxe Close" (East, adjacent) is included in "Abourfield". Information comes from the previous Lord of the Manors records (Lord Melbourne) and combines data from the 17th century)

Explanations of field names:

"Arbour": Land near or containing an earthwork

"Lady Hadland": Corrupted from of "My Lady's Headland" - church land - St Luke's also carries a dedication to "St Mary"), land dedicated to the "Blessed Virgin".

"Leys": Meadow land.

"13 Furlongs": A close consisting of 13 divisions of the former common field. In this case, "Arbour Field", the others being "Langdole Field” and "Middle Field", giving a three-field system, plus heathland on the high ground. (John Field - English Field names, 1972).

The Pale Blue Area Suggests where the Romano-British fortress may underlie, with a possible ditch, corner left at "V" alongside the footpath (of today, Abbey Street to Sixfields Stadium)

The Orange Area Suggests an outline for the later Roman town.

The Purple Feature Crossed by an ironstone railway line (I) is the approx. position of the only archaeological dig by Dr Williams in the 1970's – a fraction of the available area.

The Brown Lines (F) Are footpaths.

(WL) Is the possible water leat serving the town from Duston.

(q) Is a quarry face - the area was extensively quarried from 1853-1908, but not entirely. The railway marshalling yards in Field 50 protected some of it. Field 66 is below the ironstone and would not have been quarried.

(B) Brickyard Road - the old Duston turn - the Romano-British cemetery area and the Romano-British crossroads.

(D) The New Duston Road (moved here 1883/84)

(R-D) The Black Line The line originally thought to be the course of the Romano-British road.

(R-B) The Red Lines The most up-to-date lines showing probable course of the Romano-British road, following the receipt of Dr Williams' archaeological maps and several years of research.

For a fuller examination and review, visit Northants Record Office or Northampton Central Library Local Studies Collection and ask to see the Romano-British Map 2001 of Roman Duston (5000-1), plus the Discussion Paper - Roman Town At Sixfields, Northampton, 2001.

Please acknowledge Ordnance Survey, D.F.G. Publishing and St Luke's Archaeology, Duston if downloading.

This map and key was kindly contributed by St Luke's Archaeology (SLA).

See Also

Duston in Roman TimesRoman Road in Duston

Roman Town in Duston

Roman Finds in Duston

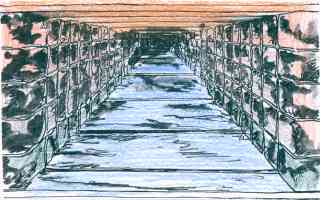

In 1996 in sewer workings at the junction of Millway and Main Road Duston, contractors cut through the old Roman road at a depth of almost 2 metres on the south side and 1.5 metres on the north side. The site was investigated over two days by St Luke's Archaeology Group (SLA).

The width of the road was about seven metres and consisted of a double stone layer of shelly upper estuarine limestone or Blisworth limestone forming the base. There appeared to be an infill binding similar to lime mortar. Over the top appeared to be a layer of large pebbles and below rammed mixed stone.

The direction was 10-20 degrees south of east, and the road appears to have been running from Bannaventa (near Whilton Lodge, Norton) on the A5 Watling Street to the River Nene crossing now known as West Bridge, close to modern Northampton.

On the section of the road illustrated by the artist's impression in the picture above, the road reached the pavement on the north side of Main Road, and was wide enough to enter Millway on the south side. Today, Main Road Duston runs in the northern ditch system of the Roman road, while the Roman road itself disappears under the Squirrels public house and adjacent cottages, emerging into Berrywood Road at its junction with Southfield Road (approximately).

Information kindly supplied by David Blackburn of St Luke's Archaeology.

See Also

Roman Town in DustonMap of Romano-British Town

Duston in Roman Times

Roman Finds in Duston

The Roman town

The Roman settlement, on a site just south of the current Weedon Road at Duston, had its origins around 25 AD when a Belgic/Celtic tribe — the Catuvellaunii — expanded into the area between several other Celtic tribal areas: Trinovantes and Iceni (east), Coritani (north), and Dobunni (west). As such it was a frontier town, typically on a southern slope by a river crossing (where Duston Mill was later built).

The presence of the settlement was detected from the discovery of a number of pottery fragments, coins and burials recorded by Samuel Sharp during the extensive quarrying of the area for iron ore and limestone during the 1800's. Unfortunately the quarrying operations must have destroyed most of the physical evidence of the occupation. The site of the settlement lies between the 200 ft and 250 ft contours alongside the western arm of the River Nene, if St Luke's Archaeology group (SLA) findings are confirmed. The burials were of several different types. Many of the Romano-British burials were to the north of this area, and there were several Anglo-Saxon ones to the west. (See also Roman Finds in Duston.)

Some time after AD 43 the settlement was Romanised. We do not know its Celtic name, nor its Romanised name, and no references to the site have yet been found in the literature or inscriptions, so we shall refer to it as 'Duston'.

(Many towns took their name from a prominent local feature. A possibility here is gravel. There are millions of tonnes in the locality, which is extracted commercially. The nearby village name of Kislingbury has been interpreted by some authorities as the 'fort of the gravel dwellers' (from the Saxon). One hypothesis is that Kislingbury may have taken its Roman name from that of Duston, as both were situated on gravel. The name Kislingbury translated back into Latin, would give us 'Glareodunum' or 'Glareodurum'.)

The town developed from Celtic/British through Roman/British to Romano/Saxon/British throughout the whole period of occupation AD 43 to AD 410 (and presumably beyond) in what appears to have been a continuous evolution until its general abandonment in the late 5th or early 6th century.

The Roman roads

The road from Bannaventa (Whilton Lodge/Norton) on the Watling Street (A5) to Duston has been historically accepted as a Roman road, and is shown as such on Ordnance Survey maps. Its line suggests that it must have passed close to the north end of the Roman settlement at Duston.The Roman road was built on the open heathland that originally existed above the 350 ft contour. St Luke's archaeology group (SLA) believe that in this terrain the Roman engineers could aim directly for their objective, unimpeded by valleys or streams. The Roman road and the roads crossing it were later used as parish boundaries in an otherwise featureless countryside. The Sandy Lane road junction is one such, bounding Upton, Harpole, and Duston. North and south, the crossroads identify the parish boundaries until streams are reached, which then take over that role.

The OS grid reference points SLA have picked out are, from the west:

- (SP 6909 6241) Near the water tower at Nobottle where the road emerges from woodland. There are sites of Roman villas in the wood, and behind the water tower. Further west the road line is lost in woodlands, valleys and following a narrow ridge.

- (SP 6977 6216) Rode Hill Harpole T-junction. Here the bridle path north leads to yet another villa site (reported by SLA recently).

- (SP 7054 6186) Sandy Lane crossroads. Heath Farm, Harpole, iron age site to the north.

- (SP 7187 6127) The back gardens of 5, 3, and 1 Berrywood Road, Old Duston, where limestone presumed to be from the surface of the Roman road has been found. Here the Main Road and Berrywood Road have been diverted from the line of the Roman road.

- (SP 7234 6102) The junction at Millway/Main Road, Old Duston. Road foundations 7 m wide and 30 cms deep were uncovered on 16/8/1996 in sewer workings, and comprised a double layer of shelly Upper Estuarine/Blisworth limestone with lime mortar infill on a rubble base.

A second road of Roman construction was investigated by Dr J. Williams in the 1970's. This passes through the site in a direction 18 degrees east of north, and comes from the direction of Towcester.

For more information, see The Roman Road in Duston.

Roman water supply

The Romans were great users of water and the native population soon became converts to the consumer society and its benefits. Duston Roman town apparently had access to a spring on its eastern flank. Variously described as a stream by Bryant, and a spring on the 1886 OS series maps. Intriguingly, the earliest map (C. Price 1722) shows it as a square or rectangle. Haverfield, in the Victoria County History, 1902, decribes it as an artificial pond. However, given the nearby presence of St James' Abbey and the 19th century brickworks we may never know what it was really used for originally.Apart from this supply the River Nene with its tributaries and springs would also be used by the population to supply reeds for thatching, fish, game, water for cattle, pigs and sheep, and for laundering needs, and the leather dressing, weaving and woollen industries. Furthermore, it is a flood plain river, and not particularly reliable as a source of drinking water. Besides, being well below the 200 ft contour, the water would have had to travel several kilometres by leat and aqueduct from a spot upriver high enough to provide sufficient head to come into the Roman town. SLA believe drinking water came from a location

The whole of Duston lies on a thick bed of Upper Lias clay, over which sand, sandstone and limestone have been deposited. In past ages this has worn away, leaving a ridge of clay exposed. As an example of the water-producing quality of the area, on the northern side in Port Road, the Duston Laundry pumped 10,000 gallons a day from one well at a constant temperature of 53 degrees F., with maximum capacity 1100 gallons per hour at a depth of 28 ft from a 13 ft sump in the clay. The water level never changed, despite the pumping, for the lifetime of the laundry. St Luke's Archaeology group (SLA) believe that the southern clay slope would provide a similar capacity from the watershed to the wells at Pond Farm Close. currently named 'Pond Farm Close' in Old Duston. Recently 10 to 12 wells have been found here 175 metres away from the start of a limestone culvert that runs underground for 100 m, and below the Roman road level, close to the war memorial.

The culvert itself is inaccessible, below ground, with a modern brickwork outlet where the Roman culvert was replaced at the end of the 20th century by a 20 inch concrete pipe, having served the Victorian engineers and later ones for some 150 years.

Approximate dimensions of the culvert are 1.5 m wide x 10 cms thick slab top, walls of 5 courses of rough ashlar, estimated at 10 cm x 25 cms deep, and a paved stepped base 60–70 cms wide by 5 cms deep. If these approximations are anywhere near, then construction would have required 1 tonne of limestone per metre length (i.e. 100 tones, plus a further 175 tonnes to Pond Farm Close.

Approximate dimensions of the culvert are 1.5 m wide x 10 cms thick slab top, walls of 5 courses of rough ashlar, estimated at 10 cm x 25 cms deep, and a paved stepped base 60–70 cms wide by 5 cms deep. If these approximations are anywhere near, then construction would have required 1 tonne of limestone per metre length (i.e. 100 tones, plus a further 175 tonnes to Pond Farm Close.From its outlet the water entered an open leat, which still runs today across Millway playing fields. It originally followed the then contours (quarried out c. 1852–1909) to the north west corner of the town.

This article was kindly contributed by St Luke's Archaeology (SLA).

See Also

Roman Town in DustonMap of Romano-British Town

Roman Road in Duston

Roman Finds in Duston

From here you can get lists of the headstones and cremation plots at Duston public cemetery with the name, inscription and plot number of each one. The information should prove helpful as a starting point for those tracing family histories or trying to locate resting-places.

Finding a Person

The information is arranged in alphabetical order by surname in the table below. The plot number and inscription are listed against each surname. Use the Search box to find a record of interest. All columns can be sorted by clicking on the column heading.No data available.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the members of the Northamptonshire Family History Society who carried out the survey exclusively for this website.Copyright

© Duston Directory, 2006Related Topics

Survey of Memorials at St Luke'sUntil the Domesday survey, Duston and nearby manors were held by the Anglo-Saxon Gytha, wife of the Earl Ralph of Hereford. Ralph was a nephew of Edward the Confessor. In 1086, the manor of ‘Dustone’ was founded by the Domesday Survey and Gytha’s lands were given to William Peverel, a mysterious figure. He is not known to have been a supporter of William I ‘The Conqueror’ in any battles and is not recorded among the Peverels in Normandy. He is said to be the illegitimate son of William I by an Anglo-Saxon girl, and was subsequently adopted into the Peverel family by her marriage to one of them. Given the nature of the feudal system, the amount of land he receives at Domesday, William’s own illegitimacy, the names he gives his own children and the final outcome two generations later, this story is almost certainly true.

The Peverel Line

There are known to have been four generations of William Peverals, referred to here as I, II, III and IV. William Peverel I, was probably born in 1052 and died in 1113. He was married to Adelina who died in 1119. William I had five children: William II died in 1100; Matilda (who was alive in 1130); William III (presumed deceased prior to 1149); Henry (who married Oddona) and Adeliza (married Richard de Rivieres). He founded Nottingham Castle and Lenton Abbey, and it appears that the Peverels were Sheriffs of Nottingham until the time of William Peverel IV.William Peverel I gave 40 acres of land on which to build an abbey (St James Abbey) at Duston, plus a wooden Church in 1103 or 1104. Henry I, the youngest son of William the Conqueror (born 1068) was friendly with William Peverel and, if we accept the story, was his half-brother. Henry I reigned from 1100 to 1135 and was a good scholar (‘Beauclerk’ was his nickname, and he is credited with the comment ‘an unlettered king is only a crowned ass ‘). It is due to his charters and recording that we begin to learn about Duston in print – he visited Northampton, possibly to check up on Simon de Senlis, William Peverel and their buildings: Northampton Castle/St. Andrew’s Priory and St. James’ Abbey respectively.

William Perverel III had two children: Henry, who predeceased his father, and William IV.

William IV married Avicia de Lancaster and supported King Stephen against Matilda and Henry II. William IV had a child named Margaret, who married William, Earl of Ferrers (Higham Ferrers). William Peverel IV, the Sheriff of Nottingham, fled on the advance of Henry II and entered a monastery in 1155. Henry II gave the ‘Honor of Peverel’ (including Duston) to Ranulf, Earl of Chester, which reverted to John ‘Count of Mortaine’ in 1174, marking the end of the Peverel line.

References

For a fuller profile of the Peverels, see Bridges’ and Bakers’ separate accounts in their ‘Histories of Northampton ‘ and look at the Peverel Society’s documents held at Nottingham Library.Article kindly contributed by local historian Dave Blackburn.

Related Topics

Duston's BeginningsRoman Period, 55BC to 410AD

With the Roman invasion in the middle of the first century AD, Britain was divided into six Roman provinces, with Duston falling within the province of Flavia Caesariensis. A fort linked to the initial military advance might have been built at Duston, and a small town was definitely established here in that period. This was part of the continuing habitation of the fertile upper Nene basin. The nature of the settlement is uncertain because of extensive 19th and 20th century ironstone quarrying that effectively destroyed much of the site.

- Coins representing the Roman emperors Arcadius (395-408) and Honorius (395-423).

- Two buckles dating to the late 4th and early 5th centuries, possibly associated with some sort of yeomanry, perhaps formed as a defensive force during the Anglo-Saxon troubles.

- A Roman lead coffin, found in the Saxon cemetery immediately west of the Roman settlement. (the cemetery may therefore have been in continuous use during both the Roman and Saxon eras.)

The Dark Ages: Early Saxon Period (c.400-650)

The Roman legions still in Britain were withdrawn to mainland Europe in the early 5th century to help defend the Empire from Germanic (Anglo-Saxon) tribes attacking the northern frontiers. The British Isles also started to suffer Anglo-Saxon attacks, which put pressure on Roman institutions here, leaving structures such as villas, baths and public buildings to fall into disrepair. Town life seems to have fallen apart, although the substantial defensive walls of the towns provided useful strongholds in times of war. Archaeological evidence shows that crude timber buildings were erected in the ruined shells of their Roman predecessors. Some towns may have become centres for emerging Saxon royal families.

The British Isles also started to suffer Anglo-Saxon attacks, which put pressure on Roman institutions here, leaving structures such as villas, baths and public buildings to fall into disrepair. Town life seems to have fallen apart, although the substantial defensive walls of the towns provided useful strongholds in times of war. Archaeological evidence shows that crude timber buildings were erected in the ruined shells of their Roman predecessors. Some towns may have become centres for emerging Saxon royal families.The Saxons divided England into kingdoms including Northumbria, Bernicia, Deira, Lindsay, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Wessex, Sussex and Kent. Duston fell within the kingdom of Mercia.

Evidence of a Saxon settlement in the Duston area, found during quarrying includes:

- Over a hundred burials in the Duston Anglo-Saxon cemetery.

- Brooches and other grave goods ranging from the middle of the 5th century onwards. Picture above shows brooch of gilded bronze from 6th century AD, found in the Anglo-Saxon cemetery in Duston in 1902. Courtesy of Northampton Museum.)

Viking Invasions (c.787)

The Vikings began to settle from about 787 onwards in the Danelaw – land to the east of Watling Street (now the A5) including Essex, East Anglia and Northumbra. Duston was therefore just within the Danelaw and became one of the chief Viking centres.The Anglo-Saxon king, Alfred the Great, started the conquest of the Danelaw with the capture of London. By 910, the Danish settlers were at war with Edward the Elder (successor to Alfred the Great), who completed the conquest of the Danelaw and by 924 had taken over the entire country.

Founding of Duston Manor

In 1066 William the Conqueror defeated Harold II at the Battle of Hastings, which marked the start of Norman rule in Britain. In 1086, the manor of ‘Dustone’ was founded by the Domesday Survey and handed to a Norman noble, William Peverel, who is sometimes said to have been the son of William the Conqueror.Before his death in 1113, Peverel founded the Abbey of St. James and gave St. Luke’s Church, Duston (which was built some time before 1113) to the Abbey. For more, see William Peverel.

References

- Saxon & Medieval Northampton by John H Williams, Northampton Development Corporation, 1982.

- A History of Old Duston and Old St. James, Northampton, by J.W.F. Golby, 1992.